Architect on a mission to save Kathmandu's soul

Subel Bhandari

KATHMANDU, Subel Bhandari - Nepal's ancient capital Kathmandu is famed around the world for its intricately carved medieval temples and ancient royal palaces.

But as the once-sleepy city hurtles into the 21st century, the distinctive architecture that visitors once flocked to see is rapidly being replaced by the high-rise concrete structures favoured by modern residents.

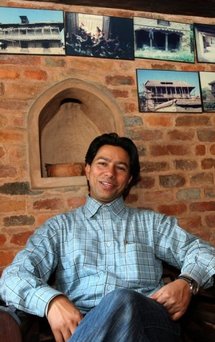

Rabindra Puri speaks during an interview in a restored 150 year-old farmhouse

Puri, a former sculptor, was struck by the city's transformation when he returned from a two-year study trip in Europe in 1995.

"My heart wept to see so many concrete buildings, they were ugly and had no substance," the 40-year-old told AFP in an interview.

"These new building models are an act of arrogance, of alienation from our history. But they are popular with the wealthy elite."

Puri had developed a passion for the traditional architecture of Nepal when he worked as a model-maker on a project to restore ancient buildings in Patan, the historic city that adjoins Kathmandu.

So, four years after his return and much to the astonishment of friends and colleagues, he quit a highly-paid job with the German government development agency to try his hand at restoring old properties.

His first case was a 150-year-old dilapidated farmhouse in Bhaktapur, around 13 kilometres (eight miles) east of Kathmandu, that for the last five years had been used to keep chickens.

The house was a classic example of the architecture of the Newars -- the indigenous inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley who are renowned for their striking brick work and unique form of wood carving.

The restoration began in 1999 and won the prestigious UNESCO Asia-Pacific Heritage Award five years later, with the judges saying it "paved the way for the conservation of similar traditional buildings throughout Nepal."

The house, which now functions as a museum as well as Puri's studio, is equipped with a modern kitchen and bathroom to show that living in an old building need not mean skimping on creature comforts.

Puri -- the first Nepalese architect to win the UNESCO award -- prides himself on reusing as many of the original materials as possible, and believes this is the secret of his success.

"The basic theory of conservation is to make only minimal change and to use traditional methods for restoring," he said. "You do not destroy anything unless it's absolutely necessary."

Since then, Puri has worked on 35 other projects, at times restoring old buildings and at times transforming the concrete structures he hates to ensure they blend in with the city's traditional architecture.

"Conservation of our cultural heritage would probably be the best way to describe what I do," said Puri, who makes no attempt to disguise his contempt for most of his colleagues in the industry.

"In the 1960s, architects and engineers who studied in Russia and India came back to Nepal. They needed to prove the worth of their foreign degrees," he said.

"They started saying that traditional designs were not strong enough and were expensive, which is the exact opposite of my experience."

In fact, Puri says, traditional buildings are often more likely to withstand earthquakes than the modern high-rises preferred by Kathmandu's wealthier inhabitants because they sway rather than collapsing.

"In the city centre you can see many traditional houses that tilt, some by as much as 15 degrees, but they do not fall over. Modern buildings often cannot handle even five degrees of inclination," he said.

"The other big advantage of living in a traditional building is that they are warmer in winter and cooler in summer."

Last year, Puri launched a conservation foundation in his own name, and he is now planning his most ambitious project yet -- the restoration of an entire town.

Panauti, 35 kilometres southeast of Kathmandu, combines architecture from the era of the Malla kings who ruled the area from the 13th century with 19th-century palaces built by Nepal's former ruling dynasty, the Ranas.

Its medieval water and sewage systems -- among the most advanced in the ancient world -- were restored in the 1990s by a group of French experts, and now Puri hopes to do the same for its buildings.

With support from local people, he hopes to restore and modernise around 700 buildings in Panauti.

"Panauti's cultural heritage has been preserved intact and it is still possible to save it from being ruined (by modern construction)," said Puri.

"In many cities, people are paid to wear traditional dress and play traditional music. But in places like Panauti, it's a way of life."

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------