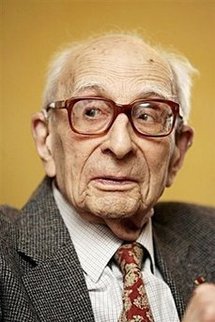

French thinker Levi-Strauss dead at 100

Carole Landry

PARIS, Carole Landry - French anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss, who helped shape Western thinking about human civilisation, has died at the age of 100, his publisher and colleagues said Tuesday.

Levi-Strauss died on Friday and was buried at a private service in the Burgundy village of Lignerolles, where he had a house, senior colleagues said.

A family friend said relatives chose to wait before announcing his death to protect their privacy and avoid a media storm at his funeral.

Trained as a philosopher, Levi-Strauss shot to prominence with his 1955 book "Tristes Tropiques" (A World on the Wane), a haunting account of travels and studies in the Amazon basin and one of the 20th century's major works.

Paying tribute, President Nicolas Sarkozy gave "homage to a tireless humanist, a curious academic who was always in search of new knowledge, to a man free of any sectarianism or indoctrination."

The French leader described him as a "very great scholar, always open to the world, who created modern anthropology and raised the reputation of French human and social sciences to its highest level."

His predecessor Jacques Chirac, who opened the Paris museum of tribal arts at Levi-Strauss' side in 2006, paid respect to "a thinker who dedicated his life to understanding and explaining cultures, their strengths, their diversity, their greatness and their fragility."

Levi-Strauss was a leading proponent of structuralism, which sought to uncover the hidden, unconscious or primitive patterns of thought believed to determine the outer reality of human culture and relationships.

Structuralism was also, Levi-Strauss liked to say, "the search for unsuspected harmonies."

French academia and the cultural elite had mobilised for his 100th birthday last year to pay homage to Levi-Strauss with a programme of films, lectures and reflection on his contribution to modern thinking.

Among the more striking conclusions of his work was the idea that there is no fundamental difference between the belief systems and myths of so-called "primitive" races and those of modern Western societies.

He was the oldest member of France's prestigious Academie of leading intellectuals, a respected but retiring figure, who had said he no longer felt at home on an overpopulated planet.

In a 2005 television interview, Levi-Strauss expressed worry about ending his days in "this world that I do not love."

"What I see are the current devastation, the frightening disappearances of living species, be they plants or animals. Because of its current density, the human species is living in a type of internally poisonous regime."

Levi-Strauss was born in Brussels in 1908, the son of French Jewish parents from the German-speaking region of Alsace. He studied philosophy and in 1935 went to Brazil, where he became a professor at the University of Sao Paolo.

He studied the lives of the tribes of the Mato Grosso and the Amazonian rainforest, collecting material for theories on the underlying structures of human relationships and myths shared by various cultures.

Returning to France in 1939 he was conscripted, but after the Nazi invasion he was, as a Jew, forced to flee to the United States, where he taught while awaiting his chance to return home and restart his career.

He was given the chair in social anthropology at the College de France in 1959, where he worked until retirement in 1982.

"Straddling the worlds of philosophy and science, his work is essential for any attempt to reflect on our society and how it works," said Denis Bertholet, one of Levi-Strauss' biographers.

"He had an ecological approach to the world and to individuals that was ahead of its time."

Levi-Strauss was married three times, and had two sons.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------