Poet urges fellow Haitians to ride out their misery

David Dieudonne

PORT-AU-PRINCE, David Dieudonne - The wall supporting his bookcase partially collapsed but the books were saved. The Haitian poet and painter Franketienne sees in the January 12 "apocalypse" a chance for a "collective awakening."

"We often waver or fall," the white-bearded playwright said in an interview, speaking slowly a syllable at a time. "But we then have to learn how to ride out our fall."

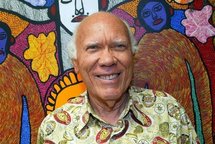

Franketienne

The tremor shook his home, nearly killing the 73-year-old poet and his wife, Marie-Andree.

Already in December, weeks before the latest disaster to hit Haiti, Franketienne placed a devastating quake at the heart of a "premonitory" play, "Melovivi" (The Trap).

"The ground sways, the ground staggers, the ground zigzags," the blue-eyed poet recited under the barely standing patio of his home in the Delmas neighborhood of the capital Port-au-Prince.

"The ground turns and capsizes. It twitches with fright and derails with terror. There's gangrene in the opera, the rats' macabre opera."

The visionary playwright, born on April 12, 1936 to a young farm woman and an American industrialist who "adopted" her before sending her back to Haiti, has penned around 30 volumes.

They include "Les chevaux de l'avant-jour" (The Horses of Dawn, 1966), "Mur a crever" (A Wall to Die, 1968) and "Ultravocal" (1972).

A true renaissance man, the poet, novelist and dramatist has also painted several thousands of works and received the Netherlands' Prince Claus Award in 2006.

He has put his life on the line in defying the regimes that have ruled Haiti in the past. In 1975, he wrote "Dezafi," an allegorical work about the political oppression that prevailed under Papa Doc's regime.

"These areas that were ravaged, it's sinusoidal," Franketienne said, pointing to parallels in the political realm.

"The minute this ravaging event took place, we saw the failure and the foolishness of our leaders, who have never had foresight and let people build any old way because they feared anger from the population."

The temblor that Franketienne foresaw and ultimately struck Haiti was a confirmation of the "esthetics of chaos" he has heralded for the past 40 years through the "spiralist" movement, he said.

But he saw in the disaster a unique chance to rebuild everything.

"It's the first time since 1804 (when Haiti gained independence from France) that all of the country's structures have collapsed," Franketienne said.

"We are at a turning point... either we wake up or it's a total collapse."

The Caribbean intellectual rejected the claims of some fellow Haitians that the massive influx of international aid is a threat to the country's sovereignty.

"Let's write, let's negotiate," he recommended. "I am not against your personal interests but make sure that mine are not completely ignored."

As for the pessimists who see in Haiti -- battered for centuries by natural disasters, political upheaval and poverty -- a land forever cursed, Franketienne shot back: "That's clearing the names of those who are truly at fault."

"When we allude to this, we are just this close to saying that it's voodoo's fault," he added. Voodoo practices are widespread in deeply spiritual Haiti.

The poet respects signs and symbols. On January 10, just two days before the quake, a voice called out at him in the early morning, enjoining him without explanation to purchase a medallion of Saint Andrew.

The darkened medallion, which Franketienne still wears around his neck like a talisman, was found by his driver in a city next to Port-au-Prince where Saint Andrew is the patron saint. The city was Leogane, the quake's epicenter.

---------------------------------------------------------------------