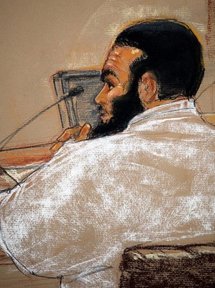

Omar Khadr

"Canada actively participated in a process contrary to Canada's international human rights obligations and contributed to Mr. Khadr's ongoing detention so as to deprive him of his right to liberty and security of the person" as guaranteed by the constitution, the high court said in its ruling.

But the lower court order was "not an appropriate remedy for that breach," it added.

"The proper remedy is to grand Mr. Khadr a declaration that his Charter rights have been infringed, while leaving the government a measure of discretion in deciding how best to respond."

US forces in Afghanistan took Khadr prisoner when he was just 15 years old in July 2002. He was later charged with war crimes for allegedly throwing a grenade that killed a US soldier.

The last Westerner at the US naval base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, he has been held at the controversial detention center for the past seven years, and is expected to face a US military trial in July.

The Canadian government has steadfastly refused to seek his repatriation, saying it preferred to allow the US proceedings to run their course.

In April 2009, a federal court judge ruled that Canada had a "duty to protect" Khadr and ordered Ottawa to seek his return "as soon as is practicable."

The decision was upheld on appeal before being argued before the Supreme Court in November.

Canadian Justice Minister Rob Nicholson said Ottawa would review the ruling before determining "what further action is required."

Rights groups demanded Khadr's immediate repatriation.

"The Supreme Court has declared (Khadr's) rights have been violated," Alex Neve of Amnesty International told reporters outside the courtroom.

"Canada has been complicit. It is not open to the Canadian government to just yawn and not take that seriously now."

In New York, the American Civil Liberties Union issued a statement saying the ruling "underscores the need for the US to reverse its decision to prosecute Omar Khadr before an illegal military commission."

"As a teenager, Omar Khadr was subjected to abusive interrogations and sleep deprivation by US officials without access to court or counsel, and with no regard for his status as a juvenile," said ACLU human rights director Jamil Dakwar.

"This is no way to treat youth in detention," he said, calling for Washington to try Khadr in a US federal court or send him home to be rehabilitated.

In its decision, the high court pointed to three interrogations of Khadr by Canadian foreign affairs and spy agency officials in 2003 and 2004, in one case after he had been deprived of sleep to make him more inclined to talk.

The extracted statements were shared with US authorities, and could "prove inculpatory in upcoming proceedings against him," it said.

As such, Ottawa's conduct "did not conform to the principles of fundamental justice" and "clearly violated Canada's binding international obligations," the high court concluded.

But it also acknowledged the government's prerogative over foreign relations.

The federal court gave "too little weight to the constitutional responsibility of the executive to make decisions on matters of foreign affairs in the context of complex and ever-changing circumstances, taking into account Canada's broader national interests," the Supreme Court justices said.

The high court also noted that it "cannot properly assess" the impact of a repatriation request on Canadian foreign relations.

Given the "evidentiary uncertainties, the limitations of the court's institutional competence, and the need to respect the prerogative powers of the executive," it chose to simply censure the government.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

But the lower court order was "not an appropriate remedy for that breach," it added.

"The proper remedy is to grand Mr. Khadr a declaration that his Charter rights have been infringed, while leaving the government a measure of discretion in deciding how best to respond."

US forces in Afghanistan took Khadr prisoner when he was just 15 years old in July 2002. He was later charged with war crimes for allegedly throwing a grenade that killed a US soldier.

The last Westerner at the US naval base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, he has been held at the controversial detention center for the past seven years, and is expected to face a US military trial in July.

The Canadian government has steadfastly refused to seek his repatriation, saying it preferred to allow the US proceedings to run their course.

In April 2009, a federal court judge ruled that Canada had a "duty to protect" Khadr and ordered Ottawa to seek his return "as soon as is practicable."

The decision was upheld on appeal before being argued before the Supreme Court in November.

Canadian Justice Minister Rob Nicholson said Ottawa would review the ruling before determining "what further action is required."

Rights groups demanded Khadr's immediate repatriation.

"The Supreme Court has declared (Khadr's) rights have been violated," Alex Neve of Amnesty International told reporters outside the courtroom.

"Canada has been complicit. It is not open to the Canadian government to just yawn and not take that seriously now."

In New York, the American Civil Liberties Union issued a statement saying the ruling "underscores the need for the US to reverse its decision to prosecute Omar Khadr before an illegal military commission."

"As a teenager, Omar Khadr was subjected to abusive interrogations and sleep deprivation by US officials without access to court or counsel, and with no regard for his status as a juvenile," said ACLU human rights director Jamil Dakwar.

"This is no way to treat youth in detention," he said, calling for Washington to try Khadr in a US federal court or send him home to be rehabilitated.

In its decision, the high court pointed to three interrogations of Khadr by Canadian foreign affairs and spy agency officials in 2003 and 2004, in one case after he had been deprived of sleep to make him more inclined to talk.

The extracted statements were shared with US authorities, and could "prove inculpatory in upcoming proceedings against him," it said.

As such, Ottawa's conduct "did not conform to the principles of fundamental justice" and "clearly violated Canada's binding international obligations," the high court concluded.

But it also acknowledged the government's prerogative over foreign relations.

The federal court gave "too little weight to the constitutional responsibility of the executive to make decisions on matters of foreign affairs in the context of complex and ever-changing circumstances, taking into account Canada's broader national interests," the Supreme Court justices said.

The high court also noted that it "cannot properly assess" the impact of a repatriation request on Canadian foreign relations.

Given the "evidentiary uncertainties, the limitations of the court's institutional competence, and the need to respect the prerogative powers of the executive," it chose to simply censure the government.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Home

Home Politics

Politics