In parallel, Jordan's King Abdullah II hosted a diplomatic push which brought together US Secretary of State John Kerry and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu for talks in Amman on Thursday.

"Recalling the Jordanian ambassador and the diplomatic push sent a tough message to Israel that violating Al-Aqsa would endanger the peace treaty," Oraib Rantawi, head of Amman's Al-Quds Centre for Political Studies, told AFP.

Kerry would not have interrupted his busy schedule and flown to the region "unless Washington realised that ties were deteriorating between Jordan and Israel, and Israel and the Palestinians", he said.

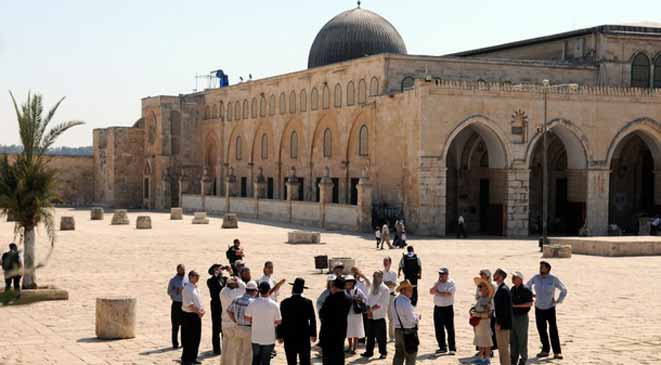

The status of Jerusalem is one of the most contentious issues in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and the Al-Aqsa compound is the scene of frequent confrontations between protesters and police.

Tensions soared to a new level earlier this month when Israeli police entered several metres (yards) inside the mosque during clashes triggered by a vow by Jewish far-right groups to visit the holy site.

"The violations at Al-Aqsa undermine the credibility and legitimacy of the Jordanian leadership and its ability to carry out its custodianship of the mosque," said Rantawi.

"It also an embarrassment towards its people, and this threatens the kingdom's stability and security," he added.

- Historic custodian -

Jordan, which has a 1994 peace treaty with Israel, is home to more than two million Palestinian refugees, as well as large numbers of Jordanians of Palestinian origin.

The Al-Aqsa compound, holy to both Muslims and Jews, is one of the most sensitive spots in the Middle East.

Israel captured Jerusalem's mostly Arab eastern sector from Jordan in the 1967 Six-Day War and later annexed it in a move never recognised internationally.

In March 2013, Palestinian president Mahmud Abbas signed a deal with King Abdullah, entrusting him with the defence of Muslim holy sites in Jerusalem.

The deal confirmed a verbal agreement dating back to 1924 that gave the kingdom's Hashemite leaders custodial rights over the Muslim holy sites.

"For Jordan, Al-Aqsa is an internal issue," said Mohammad Abu Rumman, researcher at the University of Jordan's Center for Strategic Studies, pointing to its custodianship and the Palestinian origins of many Jordanians.

The Palestinians, who make up almost half of Jordan's population of seven million, want east Jerusalem as the capital of their future state.

Jordan is seen as a key player in Israeli-Palestinian peace talks, and King Abdullah has repeatedly called on Israel to end "its unilateral action and repeated attacks" against Jerusalem's holy sites.

Rantawi said this month's clashes at Al-Aqsa had "violated the historic Hashemite trusteeship, the peace treaty and the Palestinian-Jordan deal".

- Hashemite legacy -

The Hashemites are direct descendants of the Prophet Mohammed and were in the past also the custodians of Mecca and Medina -- Islam's holiest sites in Saudi Arabia.

The history of the dynasty is intertwined with the Al-Aqsa mosque compound, where Sharif Hussein bin Ali al-Hashimi, who led the Great Arab Revolt of 1916 against Ottoman rule, is now buried.

His son, King Abdullah I, great-great-grandfather of the reigning monarch, established modern-day Jordan in 1921. He was assassinated in 1951 during Friday prayers at Al-Aqsa.

"Attacks on Al-Aqsa target the Jordanian leadership, its reputation and its relations with society," said Abu Rumman.

"They also go as far as raising questions -- on the Jordanian street and the Arab street -- over Jordan's legitimacy."

The unrest at Al-Aqsa has infuriated Jordanians and sparked anti-Israeli demonstrations and calls for Amman to break its peace treaty with the Jewish state.

It also comes after Jordan joined US-led air strikes on the Islamic State jihadist group, which has seized large parts of Syria and Iraq, prompting fears of a militant backlash.

Abu Rumman said failure by Jordan to react to "violations" at Al-Aqsa would have fanned popular discontent and raised questions over its inaction.

He said the United States had understood what was at stake, and "pressure was put on Israel".

Following Thursday's talks, Jordanian Foreign Minister Nasser Judeh told reporters "firm commitments" were made to maintain the decades-old status quo that allows only Muslims to pray at Al-Aqsa.

On Friday, Israel eased restrictions and allowed men of all ages to pray at the mosque for the first time in months.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"Recalling the Jordanian ambassador and the diplomatic push sent a tough message to Israel that violating Al-Aqsa would endanger the peace treaty," Oraib Rantawi, head of Amman's Al-Quds Centre for Political Studies, told AFP.

Kerry would not have interrupted his busy schedule and flown to the region "unless Washington realised that ties were deteriorating between Jordan and Israel, and Israel and the Palestinians", he said.

The status of Jerusalem is one of the most contentious issues in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and the Al-Aqsa compound is the scene of frequent confrontations between protesters and police.

Tensions soared to a new level earlier this month when Israeli police entered several metres (yards) inside the mosque during clashes triggered by a vow by Jewish far-right groups to visit the holy site.

"The violations at Al-Aqsa undermine the credibility and legitimacy of the Jordanian leadership and its ability to carry out its custodianship of the mosque," said Rantawi.

"It also an embarrassment towards its people, and this threatens the kingdom's stability and security," he added.

- Historic custodian -

Jordan, which has a 1994 peace treaty with Israel, is home to more than two million Palestinian refugees, as well as large numbers of Jordanians of Palestinian origin.

The Al-Aqsa compound, holy to both Muslims and Jews, is one of the most sensitive spots in the Middle East.

Israel captured Jerusalem's mostly Arab eastern sector from Jordan in the 1967 Six-Day War and later annexed it in a move never recognised internationally.

In March 2013, Palestinian president Mahmud Abbas signed a deal with King Abdullah, entrusting him with the defence of Muslim holy sites in Jerusalem.

The deal confirmed a verbal agreement dating back to 1924 that gave the kingdom's Hashemite leaders custodial rights over the Muslim holy sites.

"For Jordan, Al-Aqsa is an internal issue," said Mohammad Abu Rumman, researcher at the University of Jordan's Center for Strategic Studies, pointing to its custodianship and the Palestinian origins of many Jordanians.

The Palestinians, who make up almost half of Jordan's population of seven million, want east Jerusalem as the capital of their future state.

Jordan is seen as a key player in Israeli-Palestinian peace talks, and King Abdullah has repeatedly called on Israel to end "its unilateral action and repeated attacks" against Jerusalem's holy sites.

Rantawi said this month's clashes at Al-Aqsa had "violated the historic Hashemite trusteeship, the peace treaty and the Palestinian-Jordan deal".

- Hashemite legacy -

The Hashemites are direct descendants of the Prophet Mohammed and were in the past also the custodians of Mecca and Medina -- Islam's holiest sites in Saudi Arabia.

The history of the dynasty is intertwined with the Al-Aqsa mosque compound, where Sharif Hussein bin Ali al-Hashimi, who led the Great Arab Revolt of 1916 against Ottoman rule, is now buried.

His son, King Abdullah I, great-great-grandfather of the reigning monarch, established modern-day Jordan in 1921. He was assassinated in 1951 during Friday prayers at Al-Aqsa.

"Attacks on Al-Aqsa target the Jordanian leadership, its reputation and its relations with society," said Abu Rumman.

"They also go as far as raising questions -- on the Jordanian street and the Arab street -- over Jordan's legitimacy."

The unrest at Al-Aqsa has infuriated Jordanians and sparked anti-Israeli demonstrations and calls for Amman to break its peace treaty with the Jewish state.

It also comes after Jordan joined US-led air strikes on the Islamic State jihadist group, which has seized large parts of Syria and Iraq, prompting fears of a militant backlash.

Abu Rumman said failure by Jordan to react to "violations" at Al-Aqsa would have fanned popular discontent and raised questions over its inaction.

He said the United States had understood what was at stake, and "pressure was put on Israel".

Following Thursday's talks, Jordanian Foreign Minister Nasser Judeh told reporters "firm commitments" were made to maintain the decades-old status quo that allows only Muslims to pray at Al-Aqsa.

On Friday, Israel eased restrictions and allowed men of all ages to pray at the mosque for the first time in months.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Home

Home Politics

Politics