The first detection of the waves -- in September -- was announced in February, in a landmark discovery for physics and astronomy after decades of efforts.

On Wednesday, researchers announced they had found the waves a second time in December, produced by the collision of two black holes some 1.4 billion years ago, which sent forth a wobble that hurtled through space.

"We know from this second detection that the properties being measured by LIGO will allow us to start to answer some key questions with gravitational astronomy," said Sheila Rowan, a member of the discovery team and director of the University of Glasgow's Institute for Gravitational Research.

"Mysteries still to be explained include: how do such black hole systems form? In future we'll study this through cosmic history aiming to fill in the 'missing links' in our knowledge."

Scientists announced their findings at the meeting of the American Astronomical Society in San Diego, California this week, publishing their findings in the Physical Review Letters journal.

LIGO consists of two identical detectors sitting about 1,850 miles (3,000 kilometers) apart -- one in Livingston, Louisiana and the other in the city of Hanford in Washington state.

- 'New way' to observe universe -

Black holes form in the final stage of most massive stars' evolution. The space bodies are so dense that neither light nor matter can escape them.

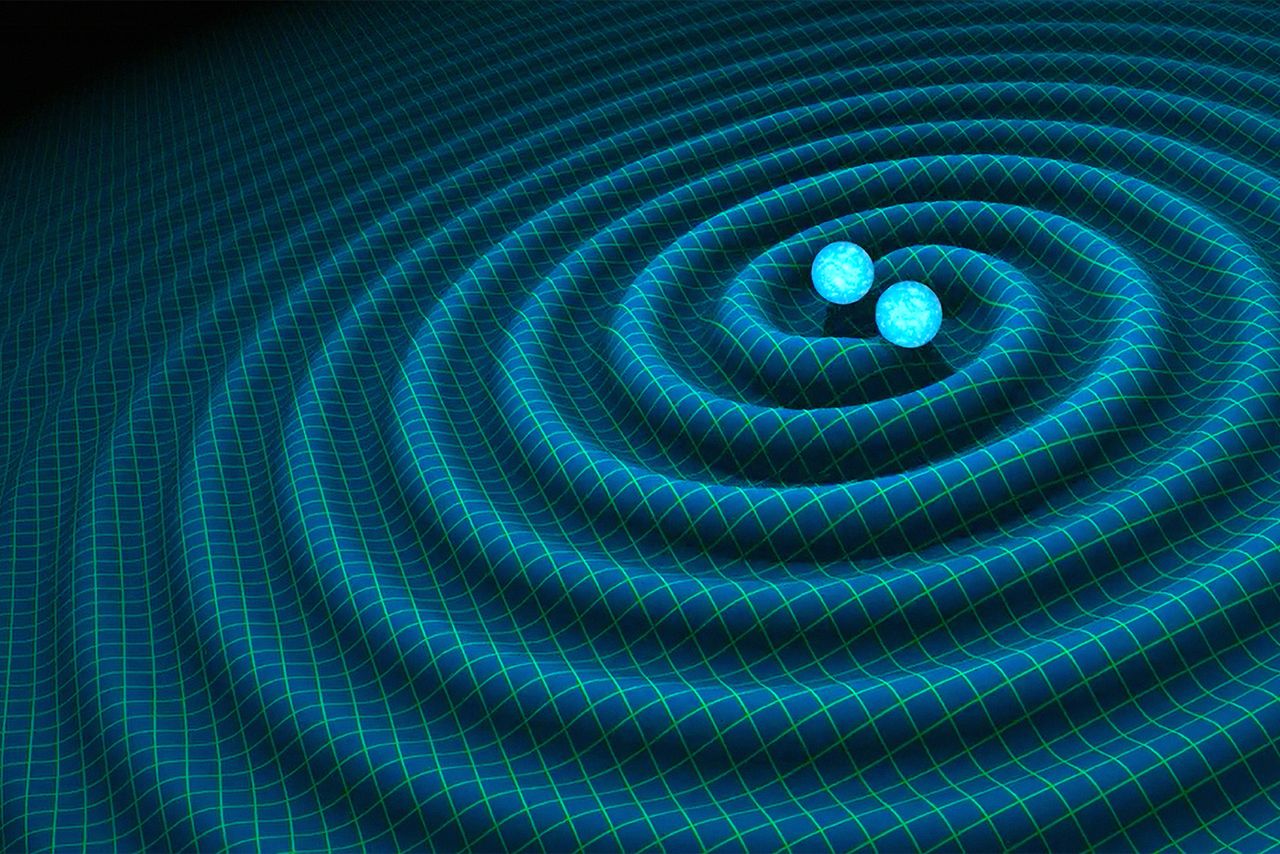

Sometimes the holes couple, orbiting in a "dance" around each other as they lose energy in the form of gravitational waves, ultimately merging into a single black hole.

Those gravitational waves allow scientists to detect when the black holes merge.

"We are starting to get a glimpse of the kind of new astrophysical information that can only come from gravitational wave detectors," said David Shoemaker, an astrophysicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and leader of the Advanced LIGO detector construction program.

Shoemaker noted that because black holes do not emit light, they are invisible except for the presence of gravitational waves.

The black hole merger generated energy that roughly equals the mass of the sun, energy converted into gravitational waves, scientists explained.

"With detections of two strong events in the four months of our first observing run, we can begin to make predictions about how often we might be hearing gravitational waves in the future," said Albert Lazzarini, deputy director of the LIGO Laboratory and researcher at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech).

"LIGO is bringing us a new way to observe some of the darkest yet most energetic events in our universe," Lazzarini added.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

On Wednesday, researchers announced they had found the waves a second time in December, produced by the collision of two black holes some 1.4 billion years ago, which sent forth a wobble that hurtled through space.

"We know from this second detection that the properties being measured by LIGO will allow us to start to answer some key questions with gravitational astronomy," said Sheila Rowan, a member of the discovery team and director of the University of Glasgow's Institute for Gravitational Research.

"Mysteries still to be explained include: how do such black hole systems form? In future we'll study this through cosmic history aiming to fill in the 'missing links' in our knowledge."

Scientists announced their findings at the meeting of the American Astronomical Society in San Diego, California this week, publishing their findings in the Physical Review Letters journal.

LIGO consists of two identical detectors sitting about 1,850 miles (3,000 kilometers) apart -- one in Livingston, Louisiana and the other in the city of Hanford in Washington state.

- 'New way' to observe universe -

Black holes form in the final stage of most massive stars' evolution. The space bodies are so dense that neither light nor matter can escape them.

Sometimes the holes couple, orbiting in a "dance" around each other as they lose energy in the form of gravitational waves, ultimately merging into a single black hole.

Those gravitational waves allow scientists to detect when the black holes merge.

"We are starting to get a glimpse of the kind of new astrophysical information that can only come from gravitational wave detectors," said David Shoemaker, an astrophysicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and leader of the Advanced LIGO detector construction program.

Shoemaker noted that because black holes do not emit light, they are invisible except for the presence of gravitational waves.

The black hole merger generated energy that roughly equals the mass of the sun, energy converted into gravitational waves, scientists explained.

"With detections of two strong events in the four months of our first observing run, we can begin to make predictions about how often we might be hearing gravitational waves in the future," said Albert Lazzarini, deputy director of the LIGO Laboratory and researcher at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech).

"LIGO is bringing us a new way to observe some of the darkest yet most energetic events in our universe," Lazzarini added.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Home

Home Politics

Politics