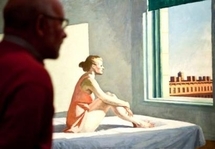

This photograph shows a visitor looking at a painting by US artist Edward Hopper, entitled 'Morning Su', during an exhibition at the Fondazione Museo in Rome.

Yet, as the 160 works assembled by New York's Whitney Museum of American Art and the Hermitage Foundation in the Swiss city of Lausanne reveal, he was also influenced by Europe, especially stays in Paris between 1906 and 1910.

Equally, the carefully-constructed urban and rural scenes of Hopper's native East Coast that made his fame after the 1930s drew on memory and were often fictional scenes that flirted with the abstract.

Carter Foster, curator of drawings at the Whitney Museum, has juxtaposed Hopper's detailed planning sketches against oil paintings, and brought in the lesser known etchings, water colours and illustrations that were his livelihood.

"This is not an exhibition of Hopper's greatest works, it's deeper than that. You see the drawings and the way his style develops step-by-step more than in some big retrospectives of his work," said Foster.

Icons of Americana such as the nocturnal street corner bar in "Nighthawks", airy wooden-housed summers of "Second Story Sunlight" are on show in Lausanne, along with interior scenes and solitary characters -- especially women.

"We use the adjective 'Hopperesque' in America, it's a well known term and it basically describes atmosphere and mood," said Foster.

Yet, early works resorted to subdued colour and were inspired by French painters Degas and Toulouse Lautrec, while a fascination for Dutch master Vermeer's use of light is evident in Hopper's self-portraits.

Hopper's stoical American figures were also preceded by more lively French 'joie de vivre' in the 1914 "Soir Bleu" and his caricatures.

"In a way if you look at him carefully he's not so American, he's more European than a lot of American artists," said Foster.

"I think he was much more influenced by Europe than most of his peers, especially at the beginning of the century."

Hopper's etchings already played with light and shadows, which became a hallmark of his career, and some early 20th century oil paintings dabbled with grayscale rather than colour.

Frederic Maire, a former director of the Locarno film festival in Switzerland, believes that visual quality created a bond between Hopper and the film world.

"From a cinematic point of view you can see the proximity, in terms of the light, the urban atmosphere, with 'film noir' thrillers," he said.

Maire's Swiss cinema archive has organised screenings of 17 Hopperesque films from 1946 to 2005, including Alfred Hitchcock's 'Psycho', Jim Jarmusch's 'Stranger than Paradise', Robert Rossen's 'The Hustler', Bob Rafelson's 'The Postman Always Rings Twice' and David Lynch's 'The Straight Story'.

Foster insists that Hopper's artistry matured faster than film did.

"So did he influence cinema, did cinema influence him? I think he had a bigger influence on later film, on film of the 50s, 60s and 70s because by then he was popular as an artist, his work was very well known," he explained.

Hopper's clarity is worthy of a snapshot and the apparent authenticity extends to keeping foreground distractions like a tree or the parapet of a balcony in a painted scene.

However, a closer look betrays flaws and the artist's attempt to toy with reality.

Shadows fall at conflicting angles, while detail from his sketches is watered down on canvas.

"He's not a realist, he's not trying to paint reality, he really isn't," said Foster, explaining that Hopper's initial visual impact serves to draw in the viewer.

"You look at the painting and understand it initially as one thing. Then you start to try to make it add up and you look at it more carefully, and it makes you realise that it's not a transcription of anything real."

The exhibition at the Hermitage runs until October 17, when the bulk of the works will return to the Whitney. The New York museum inherited Hopper's estate when his wife died a year after him in 1968.

Web link to museum: http://en.fondation-hermitage.ch/

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Equally, the carefully-constructed urban and rural scenes of Hopper's native East Coast that made his fame after the 1930s drew on memory and were often fictional scenes that flirted with the abstract.

Carter Foster, curator of drawings at the Whitney Museum, has juxtaposed Hopper's detailed planning sketches against oil paintings, and brought in the lesser known etchings, water colours and illustrations that were his livelihood.

"This is not an exhibition of Hopper's greatest works, it's deeper than that. You see the drawings and the way his style develops step-by-step more than in some big retrospectives of his work," said Foster.

Icons of Americana such as the nocturnal street corner bar in "Nighthawks", airy wooden-housed summers of "Second Story Sunlight" are on show in Lausanne, along with interior scenes and solitary characters -- especially women.

"We use the adjective 'Hopperesque' in America, it's a well known term and it basically describes atmosphere and mood," said Foster.

Yet, early works resorted to subdued colour and were inspired by French painters Degas and Toulouse Lautrec, while a fascination for Dutch master Vermeer's use of light is evident in Hopper's self-portraits.

Hopper's stoical American figures were also preceded by more lively French 'joie de vivre' in the 1914 "Soir Bleu" and his caricatures.

"In a way if you look at him carefully he's not so American, he's more European than a lot of American artists," said Foster.

"I think he was much more influenced by Europe than most of his peers, especially at the beginning of the century."

Hopper's etchings already played with light and shadows, which became a hallmark of his career, and some early 20th century oil paintings dabbled with grayscale rather than colour.

Frederic Maire, a former director of the Locarno film festival in Switzerland, believes that visual quality created a bond between Hopper and the film world.

"From a cinematic point of view you can see the proximity, in terms of the light, the urban atmosphere, with 'film noir' thrillers," he said.

Maire's Swiss cinema archive has organised screenings of 17 Hopperesque films from 1946 to 2005, including Alfred Hitchcock's 'Psycho', Jim Jarmusch's 'Stranger than Paradise', Robert Rossen's 'The Hustler', Bob Rafelson's 'The Postman Always Rings Twice' and David Lynch's 'The Straight Story'.

Foster insists that Hopper's artistry matured faster than film did.

"So did he influence cinema, did cinema influence him? I think he had a bigger influence on later film, on film of the 50s, 60s and 70s because by then he was popular as an artist, his work was very well known," he explained.

Hopper's clarity is worthy of a snapshot and the apparent authenticity extends to keeping foreground distractions like a tree or the parapet of a balcony in a painted scene.

However, a closer look betrays flaws and the artist's attempt to toy with reality.

Shadows fall at conflicting angles, while detail from his sketches is watered down on canvas.

"He's not a realist, he's not trying to paint reality, he really isn't," said Foster, explaining that Hopper's initial visual impact serves to draw in the viewer.

"You look at the painting and understand it initially as one thing. Then you start to try to make it add up and you look at it more carefully, and it makes you realise that it's not a transcription of anything real."

The exhibition at the Hermitage runs until October 17, when the bulk of the works will return to the Whitney. The New York museum inherited Hopper's estate when his wife died a year after him in 1968.

Web link to museum: http://en.fondation-hermitage.ch/

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Home

Home Politics

Politics