Jean-Claude Arnault, who is married to Swedish Academy member Katarina Frostenson, has denied the charges and allegations that came to light in November when Stockholm daily Dagens Nyheter published accounts from 18 women who accused him of sexual misconduct.

The academy, which awards the Nobel Literature Prize, has since struggled to contain the scandal - seen as a tangible example of the #MeToo movement's impact in Sweden - and several members have stepped aside or resigned.

In May, the academy announced it will not award the Nobel Literature Prize this year, citing the need to regroup and restore trust.

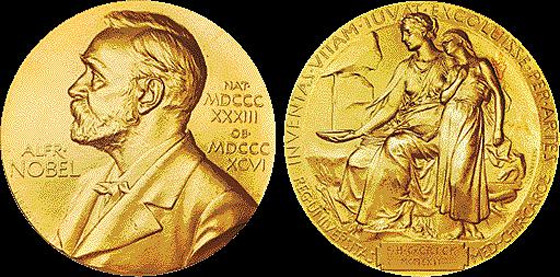

That decision was backed by the Nobel Foundation which manages the assets endowed by award founder Alfred Nobel.

"Their decision underscores the seriousness of the situation and will help safeguard the long-term reputation of the Nobel Prize," said Carl-Henrik Heldin, foundation board chairman, in a statement in May.

Thomas Kaiserfeld, a professor at the division of history of ideas and sciences at Lund University, told dpa that he doubted the Arnault trial would overshadow the upcoming Nobel award announcements, which begin on October 1.

"By postponing the literature prize the academy has bought some time," Kaiserfeld said, adding that he did not think the other prizes had been harmed.

The foundation has not commented recently on the possible ramifications on the other Nobel awards. But behind the scenes, it is believed to have engaged in a close dialogue with the Swedish Academy to promote reforms as part of its role to ensure the "standing" of the Nobel prizes.

A longer term issue would be how the Swedish Academy elects new members and from what circles, Kaiserfeld said, referring to different factions that emerged after the recent crisis.

French-born Arnault, whose trial began on Wednesday, formerly ran a performance venue partly funded by the academy. Funding ceased after the Dagens Nyheter report, and the academy also commissioned a law firm to investigate the allegations.

The sex scandal and alleged breaches of conflict-of-interest rules - including that his wife Frostenson failed to disclose that she was co-owner of the performance venue - contributed to a deep rift.

A failed bid to exclude Frostenson from the body came to light in April and highlighted the extent of the split.

Sweden has long championed gender equality - but it has not been immune to the #MeToo movement. Allegations of sexual misconduct emerged last year among other professions, ranging from the arts and stage to the legal profession.

Henrik Bjorck, a professor of the history of science at Gothenburg University, said it was hard to assess what role the Nobel Foundation had played in the decision to postpone the 2018 literature award.

"No outsider really knows," he said. "It's like quiet diplomacy, not between nations but between institutions."

Little is known of past precedents of the foundation's involvement, as the archives related to the Nobels are sealed for 50 years, he added.

But any postponement was a "clear sign" that the prize-awarding institution was unable to conduct its role with credibility, Bjorck said.

He has co-authored a history of the the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences - the body tasked with awarding the Nobel prizes in chemistry, physics and economics.

Yet he too doubted that the Arnault trial would divert much attention from the other Nobel awards.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences meanwhile said it was preparing for the award announcements as usual.

The situation in the Swedish Academy was "unfortunate," Goran K Hansson, permanent secretary for the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, said in an email to dpa.

"We are anxious that not just we, but our sister organization enjoys strong trust," he added.

Hansson said the Arnault trial could contribute to restoring trust in the Swedish Academy, but underlined that the hearing "has nothing to do with the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences."

"The announcements of the Nobel prizes in the other award categories are not affected. My coversations with research colleagues and others across the world show that trust in the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and our Nobel committees is intact," he said.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The academy, which awards the Nobel Literature Prize, has since struggled to contain the scandal - seen as a tangible example of the #MeToo movement's impact in Sweden - and several members have stepped aside or resigned.

In May, the academy announced it will not award the Nobel Literature Prize this year, citing the need to regroup and restore trust.

That decision was backed by the Nobel Foundation which manages the assets endowed by award founder Alfred Nobel.

"Their decision underscores the seriousness of the situation and will help safeguard the long-term reputation of the Nobel Prize," said Carl-Henrik Heldin, foundation board chairman, in a statement in May.

Thomas Kaiserfeld, a professor at the division of history of ideas and sciences at Lund University, told dpa that he doubted the Arnault trial would overshadow the upcoming Nobel award announcements, which begin on October 1.

"By postponing the literature prize the academy has bought some time," Kaiserfeld said, adding that he did not think the other prizes had been harmed.

The foundation has not commented recently on the possible ramifications on the other Nobel awards. But behind the scenes, it is believed to have engaged in a close dialogue with the Swedish Academy to promote reforms as part of its role to ensure the "standing" of the Nobel prizes.

A longer term issue would be how the Swedish Academy elects new members and from what circles, Kaiserfeld said, referring to different factions that emerged after the recent crisis.

French-born Arnault, whose trial began on Wednesday, formerly ran a performance venue partly funded by the academy. Funding ceased after the Dagens Nyheter report, and the academy also commissioned a law firm to investigate the allegations.

The sex scandal and alleged breaches of conflict-of-interest rules - including that his wife Frostenson failed to disclose that she was co-owner of the performance venue - contributed to a deep rift.

A failed bid to exclude Frostenson from the body came to light in April and highlighted the extent of the split.

Sweden has long championed gender equality - but it has not been immune to the #MeToo movement. Allegations of sexual misconduct emerged last year among other professions, ranging from the arts and stage to the legal profession.

Henrik Bjorck, a professor of the history of science at Gothenburg University, said it was hard to assess what role the Nobel Foundation had played in the decision to postpone the 2018 literature award.

"No outsider really knows," he said. "It's like quiet diplomacy, not between nations but between institutions."

Little is known of past precedents of the foundation's involvement, as the archives related to the Nobels are sealed for 50 years, he added.

But any postponement was a "clear sign" that the prize-awarding institution was unable to conduct its role with credibility, Bjorck said.

He has co-authored a history of the the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences - the body tasked with awarding the Nobel prizes in chemistry, physics and economics.

Yet he too doubted that the Arnault trial would divert much attention from the other Nobel awards.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences meanwhile said it was preparing for the award announcements as usual.

The situation in the Swedish Academy was "unfortunate," Goran K Hansson, permanent secretary for the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, said in an email to dpa.

"We are anxious that not just we, but our sister organization enjoys strong trust," he added.

Hansson said the Arnault trial could contribute to restoring trust in the Swedish Academy, but underlined that the hearing "has nothing to do with the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences."

"The announcements of the Nobel prizes in the other award categories are not affected. My coversations with research colleagues and others across the world show that trust in the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and our Nobel committees is intact," he said.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Home

Home Politics

Politics