"Because many Palestinians cannot reach Jerusalem, we decided to bring Jerusalem to them," said Reem Fadda, curator of the Jerusalem Lives exhibition, during a press conference on Saturday.

The museum located on the campus of Birzeit University, is a W-shaped building made of stone and glass. It opened over a year ago, but without any exhibition to show inside, leading to some ridicule.

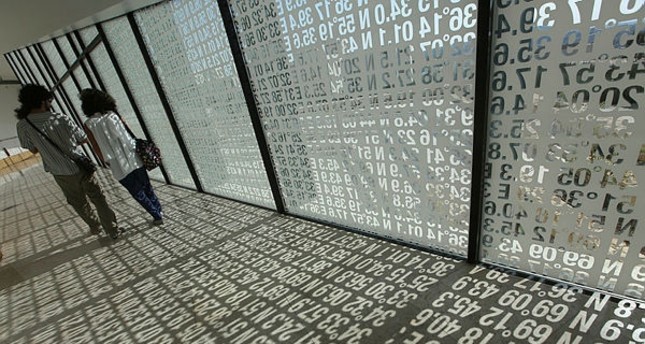

But now the first exhibition, showing until December 15, has filled the space with artwork from 48 Palestinian, Arab, and international artists, who each came with a unique story to tell about Jerusalem and its hardships. The exhibit delves into all aspects of Jerusalem through a Palestinian lens, including its culture, history, geography and politics.

Visitors to the museum are greeted by a colourful replica of the golden Dome of the Rock, the Jerusalem holy site where Muslims believe the Prophet Muhammed ascended to heaven. Jews revere the site as the location where Abraham attempted to sacrifice his son on God's command.

Last month Jerusalem witnessed two weeks of clashes that left four Palestinians dead after Israel placed metal detectors at the entrance to the holy compound that houses the Dome of the Rock. Israel said it was responding to a deadly shooting attack by Israeli Arab gunmen which killed two police officers near the site, but Palestinians saw the security measures as an Israeli attempt to impose control over the contested space.

"The Dome of the Rock represents Jerusalem. You will not find a picture or painting or any kind of art work about Jerusalem that does not have the Dome of the Rock emblem in the centre of it," Fadda said.

Fadda added that she and her team spent eight months working on the exhibition, but were hamstrung by one by-product of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: the movement restrictions on Palestinians.

"While I had to put together everything about Jerusalem in this exhibition," she said, "I was never able to get even one chance to go to Jerusalem."

While Jerusalem is only 14 kilometres from Ramallah, the majority of West Bank Palestinians, to whom Fadda belongs, need a special Israeli permit to enter the city.

Israel annexed East Jerusalem after the 1967 Six Day War, proclaiming the city as the "undivided" Israeli capital, a move that was not internationally recognized. Around 300,000 Palestinians live in the eastern half of Jerusalem.

As one walks around the museum halls, the pictures, paintings and art collections all tell a Palestinian perspective of life in East Jerusalem under Israeli occupation.

The 8-metre high concrete barrier Israel built around sections of Jerusalem in 2002 appears in some pictures and art work, and so do Israeli military checkpoints, and Israeli settlements that have mushroomed in and around the city.

Israel says it built the barrier as a security measure to prevent a wave of Palestinian suicide bombers.

Mamdouh Al Aker, board member of the Palestinian Museum, said the exhibition is a call to the world to "save" Jerusalem.

"It's a cry to the world to save Jerusalem so that this holy city will once again become a bridge for peace, not a gateway to desolation," he said.

One artist, Mona Hatom, from Lebanon, had an entire floor covered by hundreds of bars of soap showing the map of the West Bank since the signing of the Oslo Peace Accords between Israel and the Palestinians in 1993. The map of the West Bank mimics Swiss cheese, with the area fragmented by Jewish settlements.

Many in the international community consider Israeli settlements illegal under international law and an obstacle to peace between the Palestinians and Israel because they impede the viability of a contiguous Palestinian state.

Still, the exhibition does also deal with less political subjects, including colourful paintings that portray Jerusalem as an open city.

Dutch artist Athar Jaber created an interactive installation in the museum's garden that plays off the ubiquitous Jerusalem stone, which covers the holy city in an off-white hue.

"I don't want to divide Christians, Muslims and Jews," Jaber told dpa, "I hope that all religions can find something in the stone. That it speaks to them."

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The museum located on the campus of Birzeit University, is a W-shaped building made of stone and glass. It opened over a year ago, but without any exhibition to show inside, leading to some ridicule.

But now the first exhibition, showing until December 15, has filled the space with artwork from 48 Palestinian, Arab, and international artists, who each came with a unique story to tell about Jerusalem and its hardships. The exhibit delves into all aspects of Jerusalem through a Palestinian lens, including its culture, history, geography and politics.

Visitors to the museum are greeted by a colourful replica of the golden Dome of the Rock, the Jerusalem holy site where Muslims believe the Prophet Muhammed ascended to heaven. Jews revere the site as the location where Abraham attempted to sacrifice his son on God's command.

Last month Jerusalem witnessed two weeks of clashes that left four Palestinians dead after Israel placed metal detectors at the entrance to the holy compound that houses the Dome of the Rock. Israel said it was responding to a deadly shooting attack by Israeli Arab gunmen which killed two police officers near the site, but Palestinians saw the security measures as an Israeli attempt to impose control over the contested space.

"The Dome of the Rock represents Jerusalem. You will not find a picture or painting or any kind of art work about Jerusalem that does not have the Dome of the Rock emblem in the centre of it," Fadda said.

Fadda added that she and her team spent eight months working on the exhibition, but were hamstrung by one by-product of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: the movement restrictions on Palestinians.

"While I had to put together everything about Jerusalem in this exhibition," she said, "I was never able to get even one chance to go to Jerusalem."

While Jerusalem is only 14 kilometres from Ramallah, the majority of West Bank Palestinians, to whom Fadda belongs, need a special Israeli permit to enter the city.

Israel annexed East Jerusalem after the 1967 Six Day War, proclaiming the city as the "undivided" Israeli capital, a move that was not internationally recognized. Around 300,000 Palestinians live in the eastern half of Jerusalem.

As one walks around the museum halls, the pictures, paintings and art collections all tell a Palestinian perspective of life in East Jerusalem under Israeli occupation.

The 8-metre high concrete barrier Israel built around sections of Jerusalem in 2002 appears in some pictures and art work, and so do Israeli military checkpoints, and Israeli settlements that have mushroomed in and around the city.

Israel says it built the barrier as a security measure to prevent a wave of Palestinian suicide bombers.

Mamdouh Al Aker, board member of the Palestinian Museum, said the exhibition is a call to the world to "save" Jerusalem.

"It's a cry to the world to save Jerusalem so that this holy city will once again become a bridge for peace, not a gateway to desolation," he said.

One artist, Mona Hatom, from Lebanon, had an entire floor covered by hundreds of bars of soap showing the map of the West Bank since the signing of the Oslo Peace Accords between Israel and the Palestinians in 1993. The map of the West Bank mimics Swiss cheese, with the area fragmented by Jewish settlements.

Many in the international community consider Israeli settlements illegal under international law and an obstacle to peace between the Palestinians and Israel because they impede the viability of a contiguous Palestinian state.

Still, the exhibition does also deal with less political subjects, including colourful paintings that portray Jerusalem as an open city.

Dutch artist Athar Jaber created an interactive installation in the museum's garden that plays off the ubiquitous Jerusalem stone, which covers the holy city in an off-white hue.

"I don't want to divide Christians, Muslims and Jews," Jaber told dpa, "I hope that all religions can find something in the stone. That it speaks to them."

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Home

Home Politics

Politics